The unfortunate reality for most modern parents is that most parents will go through a period where they regret having kids. Particularly in today’s world where parents and kids are forced to quarantine in their own homes for long, winter months.

But guess what? This is not because they are bad parents.

This is just because the current socio-economic/capitalist system that predominates the world was never designed to make parenting easy.

So how did we get to this point where so many parents feel overworked and stressed to the point that they regret having children?

Continue reading below to learn more.

Simple. We never evolved for raising children by ourselves.

humans evolved in an entirely different socio-economic system where one child had many more “parents” than they do today. In hunter-gatherer days, whole villages took care of kids. Most parents had several kids, but only one to two survived. Parents also lived in close proximity to each other, so it was very easy to have your kids cared by one parent in the village for the day as you went hunting or gather for the day. A wide array of relatives were always at hand to take care of children - aunts, uncles, grandparents, etc. Anthropologist Sarah Hrdy found that among foraging cultures, human babies had contact with over twenty individuals every day, and the more contact they had, the more likely they were able to flourish. The intense demands of the human baby actually evolutionary selected for humans that were able to communicate and coordinate tasks for infant caring (Hrdy, 2011).

this is one reason why humans have such a long lifespan. Why is it that an animal on earth lives nearly half of its life without the ability to procreate (post-menopause)? From a strictly rational/evolutionary standpoint, it doesn’t make sense. They are a drain on resources if they don’t procreate or produce food. And weakening muscle mass doesn’t certainly doesn’t make ideal hunters OR gatherers. So why keep grandparents around? For one reason: raising children.

human babies are born helpless, in stark contrast to most other animals. Most animals are born with an inborn set of skills. Baby giraffes, for instance, are born with an instinctual ability to stand just seconds after being born. Human babies, however, take 1–2 years before being able to do such skills. They also take years of contact and teaching to learn basic skills such as speaking, remembering, planning, and strategizing. They take nearly 20+ years before becoming fully self-sufficient (some may argue even longer). In fact, some may argue that in today’s economy, this number just keeps increasing. The reason is that human life is complicated, full of delicate skills such as speaking, interacting, sizing-up, competing, laughing, engaging, conflicting, cooperating, etc., that it just takes a long time for any organism to learn.

Children were designed to be cared for by multiple “parents”. Grandparents, aunts, uncles, family friends, you name it. We are a social species that was designed to help each other do parenting.

It takes a village, and that’s just the truth.

Alloparenting - the word used to describe the action of parenting children not one’s own - has been linked to the emergence of numerous human traits that de-linked us from our ape cousins.

It also has been linked to boosting the confidence of mothers (Fleming et al., 1997), prenatal feelings of competence, positive attitudes towards parenting in general (Fleming et al., 1998), and efficiency in childcare in general (Leerkes and Burney, 2007).

In contrast, most other animals including chimpanzees rarely engage in alloparenting with the exception of a few (certain bird species, primates, African wild dogs, etc).

In nearly all species, we see individuals more likely to help kin versus non-kin, but back in the day, most of the village was genetically at least somewhat close to the individual. True strangers in a village were rare. So villagers all helped each other, and this enabled the species to thrive and raise healthy children.

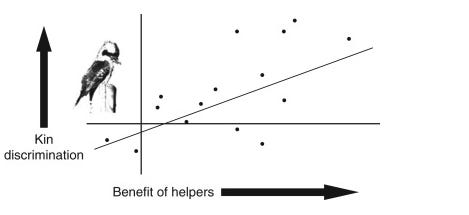

Fig. 4. Griffin and West (2003) measured the effect of helpers on the reproductive success of breeders across species (benefit of helpers) and correlated it with the extent to which helpers discriminate with respect to kinship when making decisions about helping. This analysis showed that species with more helpful helpers were more likely to direct their aid preferentially towards related young. Each point of the graph represents the value for a single species.

Unfortunately, our current society actively works against the alloparenting instincts that are inborn within us. Upon graduating from high school, we are expected to leave our families and find a new location to study or work. This cultural push is particularly strong in the U.S. but is increasingly seen in cultures around the world. Our urban areas still lack adequate green spaces for meeting others. People in dense areas report elevated feelings of depression relative to benchmarks, and even wealthier areas are more likely to feel depression relative to non-wealthy areas (Oliver, 2003). This very likely due to the fact that wealthy individuals must sacrifice work over family considerations, although in today’s world (i.e. 2020s) it’s very likely that individuals from all classes are feeling more alienated and less connected to their neighborhoods than before.

So next time you feel exhausted, burn out, or ready to tear your hair out, don’t blame yourself. Don’t blame your kids.

Blame the system.

Sources:

Fleming, A. S., Ruble, D. N., Flett, G. L., & Shaul, D. L. (1988). Postpartum adjustment in first-time mothers: Relations between mood, maternal attitudes, and mother-infant interactions. Developmental psychology, 24(1), 71.

Fleming, A. S., Ruble, D., Krieger, H., & Wong, P. Y. (1997). Hormonal and experiential correlates of maternal responsiveness during pregnancy and the puerperium in human mothers. Hormones and behavior, 31(2), 145-158.

Hrdy, S. B. (2011). Mothers and others. Harvard University Press.

Kenkel, W. M., Perkeybile, A. M., & Carter, C. S. (2017). The neurobiological causes and effects of alloparenting. Developmental neurobiology, 77(2), 214–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/dneu.22465

Kennedy, G. E. (2005). From the ape's dilemma to the weanling's dilemma: early weaning and its evolutionary context. Journal of human evolution, 48(2), 123-145.

Kishimoto, T., Ando, J., Tatara, S., Yamada, N., Konishi, K., Kimura, N., ... & Tomonaga, M. (2014). Alloparenting for chimpanzee twins. Scientific reports, 4(1), 1-8.

Leerkes, E. M., & Burney, R. V. (2007). The development of parenting efficacy among new mothers and fathers. Infancy, 12(1), 45-67.

Oliver, J. E. (2003). Mental Life and the Metropolis in Suburban America: The Psychological Correlates of Metropolitan Place Characteristics. Urban Affairs Review, 39(2), 228–253. Mental Life and the Metropolis in Suburban America: The Psychological Correlates of Metropolitan Place Characteristics - J. Eric Oliver, 2003